Southeast Texas Veterans Bios “Last of the Greatest” Series. Lester Trauth Sr. WWII

World War II Veteran Biographies Southeast Texas

Remembering Lester Trauth Senior – US Army D-Day Veteran

In honor of our Southeast Texas Veterans, we will be sharing some of our favorite interviews with Golden Triangle senior veterans.

Our SETX Seniors “Last of the Greatest” series continues today with a profile of Lumberton World War II veteran Lester Trauth Sr.

Lester is a US Army veteran of the European campaign and a D-Day Veteran.

His World War II experience is like a real life “Saving Private Ryan”.

Lester Trauth (pronounced Trout) Sr. enlisted in August of 1943 in Louisiana. He was told he was significantly underweight for the US armed forces, but a recruiter bent the rules saying, “Oh heck, let him join the Army – we’ll fatten him up”.

Trauth underwent boot camp at Camp Beauregard in Louisiana and underwent additional training at Camp Gruber near Muskogee Oklahoma with the 42nd Infantry.

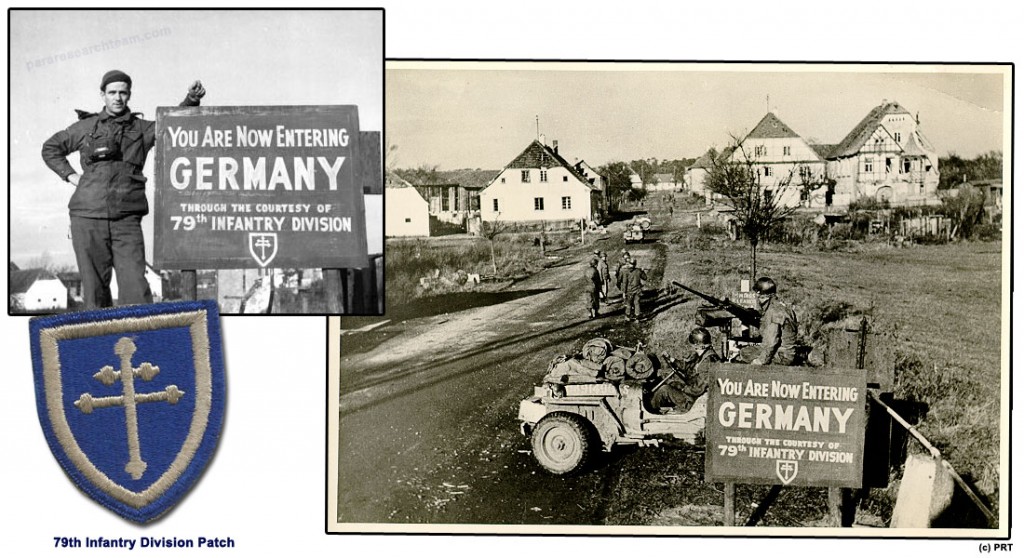

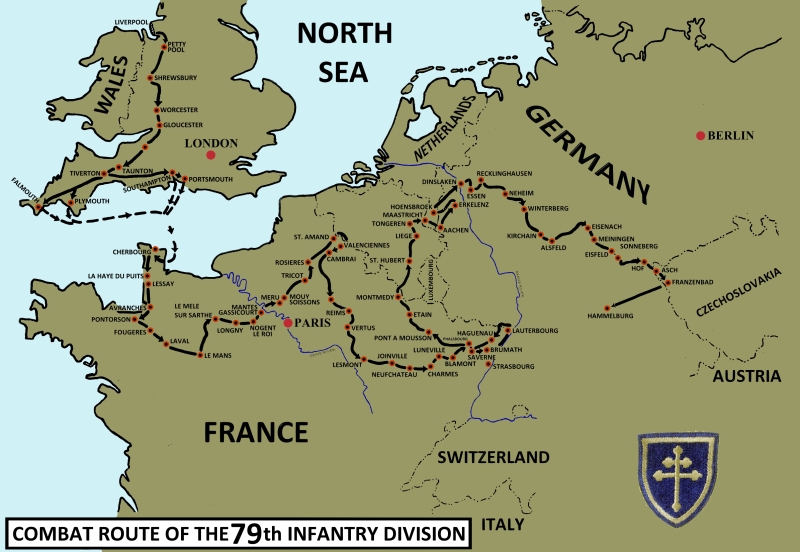

The 42nd Infantry was disbanded and Trauth was absorbed into the 79th Infantry that was mustering for the European theater of operations.

Trauth caught up with the 79th Infantry in Camp Phyllis Kansas.

The 79th was moved to Camp Myles Standish near Boston for staging to Europe. Trauth boarded the RMS Strathmore, a fine British luxury liner (though overcrowded on this voyage with American troops) for a very quick five day Atlantic crossing from Boston to Glasgow Scotland. Designed to carry 1,000 passengers, the Strathmore was packed with 5,000 US troops to assist England and our allies in their time of greatest need. The HMS Strathmore was the fastest of the ships in the convoy and had been given orders to sprint ahead alone if there were any signs of German U-Boat activity to protect the US Troops.

From Glasgow, Lester Trauth and the 79th proceeded by train into England. They were stationed in England enjoying a last period of relative safety before the European invasion. Sundays included trips to a local amusement park, restaurants, and relative leisure.

By this point, the British were exhausted from the long bombing campaign against the UK by the German Air Force. Some of the frustrated British troops referred to the incoming Americans as “Over paid, over sexed, and over here”.

The ribbing went both ways though. Each night the bars closed with a playing of “God Save the King”. Some rowdy American GIs couldn’t help but chant “If not for the Americans, God Help the King!” Predictably, scuffles immediately followed.

In England there were warm beds, cooked food, and regular downtime.

Lester Trauth turned 19 in England.

Shortly, that period of Trauth’s World War II experience ended.

Trauth was part of the D-Day invasion, landing at Utah Beach.

During the hedge fighting on D-Day, one of his companions was bothered by not being able to see. Unable to stand it any longer, he darted up to get a look and was shot in the head by a German sniper. In one of the freak coincidences of war, the bullet grazed his entire scalp digging a furrow into the top of his head without killing or even seriously injuring him. It scared him though, after that he decided he, “Didn’t care if he could see anything or not” for the rest of his war.

Lester’s own first near miss occurred when a German potato masher grenade knocked over a nearby American mortar. He narrowly missed being killed in the explosion.

Trauth’s unit was part of the liberation of the French city Cherbourg.

Lester spent time in a war hospital in Nancy when his ribs were shattered by shrapnel from a German artillery shell. While his ribs were broken, Trauth did not receive a Purple Heart. At the time the designation was “shed blood” and the injury broke his ribs without breaking the skin. Ironically Lester did shed blood when the army doctor ripped a great deal of skin off removing his bandages.

This injury wasn’t Trauth’s only brush with death, or with German artillery.

In one incident, he’d taken off his large army overcoat that he dubbed his “horse blanket” and wrapped it up tightly and packed it in his backpack. A German mortar shell exploded and a shrapnel fragment tore through Lester’s backpack, mess kit, his extra pair of socks, field radio batteries, his emergency MREs (including a Hershey bar) and halfway through his folded backpack- all at the center of his backpack. If he had been carrying one less item, the shrapnel would have shattered his spine.

In another instance, German shrapnel shattered the stock on his M1 rifle.

Lester Trauth and the 79th had impressive views of dogfights in the air overhead as the newly arrived American pilots dueled the German’s for mastery of the skies. In one memorable dogfight two brand new American P51s engaged three ME 109s. The German pilots weren’t accustomed to the enhanced maneuverability of the P51 (their fighters had been faster and turned more tightly than the British Spitfires or American P47s). Desperate to dodge the American fighters, two of the Germans crashed into each other and exploded. The third was shot down by an American and glided into the American storage dump on the ground sending up a huge explosion when it set off stored ammunition and artillery shells.

The campaign across France, Austria, and Germany was a tough one.

Lester Trauth and the 79th served ten months straight in combat, much of it behind enemy lines.

There were many times when they were pinned down by German artillery and infantry fire. They came to really appreciate the Army Air Corps. Trauth said, “We’d radio for support and those P-47s would come running. Between their bombs and machine guns the Germans would get quiet pretty  quickly”.

quickly”.

Of course, in those days dropping bombs wasn’t an exact science and sometimes when you call in for “close air support”, close is what you get. Trauth said, “Sometimes after the P-47s came the bombs would drop close enough that we couldn’t hear anything for a while”.

Like most infantrymen in war, Trauth saw plenty that he’d just as soon forget. The Germans fought a long time and were well armed. Nothing in the campaign came easy.

One day on the Seine, Trauth’s Lieutenant saw a German soldier sunbathing across the river. He took a snap shot at the German, terrifying him but not wounding him. The German hopped up and sprinted into the safety of the woods.

Soon German 88s opened up and started to shell the American side of the Seine.

When the American artillery opened up, the Germans quickly stopped firing and ran to the river to surrender.

Trauth found himself in an odd position. He was standing on one side of the river with a much larger group of Germans on the other side with their hands up waiting to take prisoner, “We didn’t even have a way to get to them. It was the funniest thing ever. They wanted to surrender and we couldn’t get to them. If they wanted to, they could have just walked away and we couldn’t have done anything to them. They didn’t want to walk away though. They were through with the war. They’d had all they wanted.”

Lester was able to commandeer a French boat and ferry the Germans back to the American side of the river for surrender.

When they interrogated the Germans, part of the reason for the quick and determined surrender became apparent. The Germans were mostly old men and young boys. An older German artillery man who spoke some English asked, “When did the Americans invent automatic artillery?” There were so many US artillery pieces firing so quickly that the experienced artillery man was convinced we’d invented some kind of next generation automatic cannon. When Trauth said we hadn’t invented anything of the sort, he expressed disbelief, “We were taking in twenty American shells for each one we managed to fire”.

When they came into German towns, they were surprised at the differences in what they saw.

Most towns were bombed to rubble. Empty wastelands, piles of bricks lining empty streets.

Heidelberg was the exception. Trauth and the 79th Infantry were told that the town had been spared because the German universities were there. After seeing so much ruin, it was surreal to see a “whole” town again.

When they went to Stuttgart, the whole town had been destroyed by the exhaustive allied bomber campaign. The city was like one built by a child by blocks after the child threw a tantrum and demolished it. There was one large intact building, a beautiful old cathedral. Trauth never learned if the cathedral was left standing by allied benevolence (and luck as bombs weren’t very accurate) or by divine intervention.

When they went to Stuttgart, the whole town had been destroyed by the exhaustive allied bomber campaign. The city was like one built by a child by blocks after the child threw a tantrum and demolished it. There was one large intact building, a beautiful old cathedral. Trauth never learned if the cathedral was left standing by allied benevolence (and luck as bombs weren’t very accurate) or by divine intervention.

Most churches weren’t so lucky. Early in the war, the US caught on to the German preference of setting up observers (and sometimes snipers) in church steeples. For the mechanized support arm of the 79th infantry, one of their first missions upon entering any new town was to send a tank in to shoot out the church steeples.

Churches weren’t the only hiding spot favored by German snipers. One German sniper was tied into a tree and intent on inflicting major damage. One of Trauth’s comrades seized a bazooka and blew up the whole tree, sniper and all. Due to the unusual firing angle, he caught his own pants on fire.

During the campaign, occasionally new troops were sent in. Sometimes they were sent in form the American stockade in England. They were offered a choice of finishing out their entire sentence stateside or on the front lines. Most chose the front lines. Trauth remembers one, George Cortez, showing

up fresh from the stockade, all sunglasses and attitude. At night when Trauth and the others went to dig their slit trenches, he refused, saying he’d just as soon sleep on the ground. When the sun went down, the new recruit was introduced to the German practice of shelling the American position all night to keep them from resting. Trauth laughed and said, “You could see Cortez like a gopher in the moonlight, dirt flying everywhere with his shovel going a mile a minute”.

With artillery, aircraft, and small arms the US troops became keenly aware of the differences in sound. Trauth and his comrades could instantly tell the difference between a German burp gun and GI’s Tommy gun. They could also identify the sound of an oncoming aircraft as a German ME 109 or American P-47 Thunderbolt or P-51 Mustang. Sometimes it was tempting to pick up a German weapon like the burp gun and use it, but it wasn’t without risk of inviting friendly fire from GIs who immediately associated the sound with German troops.

One German plane they knew well was nicknamed “Bed Check Charlie” by Lester and the 79th. He’d fly over the allied position each night at dusk. A wall of anti aircraft fire would come up, thousands of tracer rounds from the big 50 caliber anti-aircraft emplacements. Day after day, Bed Check Charlie would escape unharmed. Finally, the day Big Crosby and Bob Hope came to play for the troops his luck ran out and he was downed by American fire.

Towards the end of the war, the 79th started to notice that they were more often facing older men and younger boys. Germany didn’t have enough elite troops left.

In addition to the danger of combat, being on the front lines brought other discomforts.

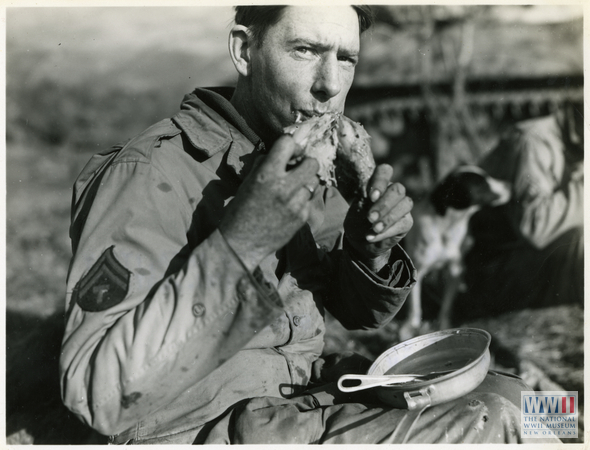

I think Mr. Trauth resents army cooks as much as the enemy soldiers. In his ten months of combat duty, his unit only saw army cooks twice. The rest of the time, the cooks were well back from the lines and each meal was either army rations or food scrounged from the empty towns and villages they took over.

One of the times the cooks came forward was Thanksgiving Day. Cruelly Trauth was called for patrol. Unable to stand it, he ran back and grabbed a turkey leg and ate it on the march.

Another time, they had crossed the Seine and believed it to be safe. The army cooks came forward, but when the German artillery pushed back, the cooks disappeared again for the remainder of combat operations.

In one village, tired of field rations, Trauth caught a French chicken, cleaned it, and roasted it.

One valued member of the 79th Infantry was nicknamed “The Big Time Operator”. He had a reputation for sniffing out abandoned food stores and wine cellars left behind when the villages and towns were abandoned. These provided a welcome break from the monotony of field rations.

Another inconvenience was the inability to take a bath or shower. At times during their combat tour, two months would pass between bathing opportunities.

There were some amusing times, despite the dangers and hardships of life on the front lines.

In one deserted town, the men had taken shelter in an old building. Most rested in the common area, while some explored. Trauth gave a word of warning to another soldier, “Look out behind you!” The GI spun around to see a rapidly approaching German soldier. Before things got out of hand he recognized the “German” was a fellow GI who had found a stock of German uniforms in the basement.

In another town, the 79th Infantry was holed up in an old church. One of the men dusted off the piano and they enjoyed a rare treat, live American boogie woogie music.

Music wasn’t always appreciated. In another abandoned building there were a bunch of box springs with no mattresses. Still, it was a step up from a fox hole, so most of the men got “comfortable” on a set of box springs and tried to get to sleep. One of the men though found an old Victrola and a single record that he played over and over all night – and the record was in French.

Towards the end of European hostilities, after ten months straight in front line combat Trauth was happily transferred to the 516th MP battalion where he served out the rest of World War II as a military policeman. Directing traffic was a welcome break from month after month of seemingly endless incoming German artillery barrages.

The duty was also comparatively light. A six hour shift every other day. Actual meals prepared by army cooks who finally showed up after the danger had passed.

For a while Trauth had the best duty of all, guarding the WACS barracks. After almost a year on the front lines, what more could a young infantryman ask for?

Most of his experiences as an MP were a welcome break from his days on the front lines.

The only thing he spoke poorly of was a couple of new officers who showed up after missing the whole war to, “do things by the book”. Combat experienced enlisted men weren’t impressed.

One newly arrived officer snuck up on an MP post and caught an MP napping and turned him in. The officer was trying to enforce a reputation of doing everything “the army way”.

The officer decided he was going to make that a regular thing and when he tried to sneak up on his next post, the MP put a bullet through his hat and then called for him to identify himself.

That officer soon disappeared.

As an MP, Lester T rauth found himself assigned to Heidelberg Germany, his ancestral home. His family had come full circle.

rauth found himself assigned to Heidelberg Germany, his ancestral home. His family had come full circle.

In 1844, Trauth’s family left Heidelberg for the United States in search of a better life.

In 1944, one hundred years later Trauth had returned from America to give Europeans a better life.

At the end of the war, Trauth was a US Army corporal.

He was awarded four battle stars and the combat infantry badge.

He was returned to the US, not by British luxury liner, but by a much slower “Liberty Ship” that took eighteen days to make the same voyage that had taken five days on the HMS Strathmore.

Trauth has been a member of the American Legion for 66 years with Post 222 out of Marrero LA.

He has been a member of the VFW for over 50 years with Post 7307, also in Marrero.

For much of the war, Trauth had a friend from boot camp. Eduardo Botello. Eduardo was a Texan from Laredo who Trauth buddied up with. Trauth was awarded two purple hearts. In the last leg of their European campaign Botello was ordered north when Trauth was ordered south.

For twenty years, they didn’t see each other or even communicate until Trauth’s son, Lester Jr. was headed to Vietnam. Trauth looked up his old friend who now lives in San Antonio with his daughter. Today they communicate regularly.

Both men will turn 89 this year.

Trauth’s eldest son is Lester Trauth Jr. who served in the Air Force during Vietnam.

Lester Trauth Jr.’s story will be told in an upcoming article here on SETX Seniors.com.

Spending a few minutes with Trauth reinforces all of our ideas of what World War II was about.

Young men given a rare opportunity to make a real difference on the World Stage.

Men taken from farms and small towns and American cities and thrust into an environment that would make them heroes.

Thank-you to Lester Trauth for his service to our nation.

We greatly enjoyed the time Trauth spent with us and are excited to profile him in our “Last of the Greatest” series featuring veterans of WWII.

We hope you enjoyed today’s featured Southeast Texas World War II Veteran Biography.

- Daryl Fant, Publisher. Southeast Texas Senior Magazine, Online at SETXSeniors.com

- (512) 567-8068

- SETXAdvertising@gmail.com